By Linda Cicoira

Photos Courtesy of Raenelle Zapata

The sophisticated Washington, D.C., attorney Raenelle Humbles Zapata got her assertiveness from the Eastern Shore community where she grew up.

“Everybody would tell you how great you are,” she said. “What kind of confidence does that give a kid? That gives you the confidence to slay dragons. I’m very proud to have grown up when I did. Because you really did try to do your best. Always. That was excellence.”

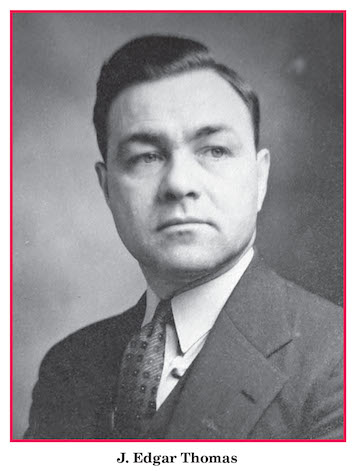

She says her heart and soul still belong to the former Tasley Fair where she spent memorable childhood days adoring her grandfather, J. Edgar Thomas, who owned and operated the place in the 1950s.

The 48-acre site is now farmland near the busy traffic circle and is still in the family. The grandstand and other buildings are long gone. But those who attended the fair can still picture it all as they ride by.

It was famous for “people coming together and having a good time,” said Zapata. “It was famous for making sure folks would always be able to congregate. Families would have their reunions that week. Everybody would be home.” People came from places as faraway as New York City and Florida. “We had a friend who was a pianist. He worked on St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. When and if he came home he would fly in for fair week.”

Zapata spent so much time with her grandfather in the early days when she was “five, six, and seven” that she had a cot in his office at the fairgrounds. Her mother and grandmother were teachers and when they weren’t working at school, they were busy working at the fair, doing household chores, or cooking meals for the family.

Zapata spent so much time with her grandfather in the early days when she was “five, six, and seven” that she had a cot in his office at the fairgrounds. Her mother and grandmother were teachers and when they weren’t working at school, they were busy working at the fair, doing household chores, or cooking meals for the family.

“I would sit on a handkerchief on his shoes while he was conducting business,” she said reminiscing. “It was really the golden era of the fair.” There was harness racing, a Russian bear trainer and his son, a fortune teller, a photo booth, beer gardens, games, food, and rides.

“I would ride with my grandfather all over the county, Accomack, and Northampton, and to Dewey, Del., to put up place cards,” she said. “We did legitimate harness racing” overseen by a judge who “looked just like Colonel Sanders — string bowtie, white hat, and white suit. He and his daughter, who was the tallest woman I ever saw in my life, would come up from Kentucky.”

The colonel came to a formal dinner at her house where champagne was served. She remembers drinking ginger ale in her glass. “They would discuss fair business and family stuff.” His daughter “was very kind to me. She would give me puzzles to keep me occupied during the day. I would help her to get ready for the races. I basically had an unusual childhood. So many interactions for growing up on the Eastern Shore.”There was “The Man from Borneo, a crazy white guy throwing a dead chicken around,” and “Sam the Ice Cream Man, an Italian from New Jersey. He had the best frozen custard.” Another guy sold fried hard-shelled crabs, which she never tried.

An old-fashioned medicine man came every year driving a big Cadillac with a trunk full of snakes, she said. “Rattlesnake Bill from Vinegar Hill. He never got bit and he never will. He wore a big hat with a feather in it. A big guy. Part Native American with two long braids. He sold snake oil, liniments and stuff.”

There was also a sideshow, she remembered, with conjoined twins who were 13 or 14 and were attached at the hip and side. They sat in a tent and people would come to gawk at them.

“My mom had a novelty stand. She sold novelties and balloons. She and another teacher. Whistles and all. I used to pump up the balloons.” Another family stored their stand at the fairgrounds. “They would come in and do nothing but sell french fries,” she said. “I know they made tons of money because the lines were always there.”

Local people had stands that sold lunch and dinner. The beer garden was in a one-story barn with booths and a huge jukebox. “It was like a nightclub. Oil cloths were put on the tables and everything would be painted up every year. I was not allowed to go in there after 5 p.m.,” said Zapata. The “hootchy-kootchy” show amounted to dancers and was set up at the far end of the fair and was for adults only.

Local people had stands that sold lunch and dinner. The beer garden was in a one-story barn with booths and a huge jukebox. “It was like a nightclub. Oil cloths were put on the tables and everything would be painted up every year. I was not allowed to go in there after 5 p.m.,” said Zapata. The “hootchy-kootchy” show amounted to dancers and was set up at the far end of the fair and was for adults only.

“The same carnival came every year. The carnie guy’s name was Sylvester. They had the midway. I used to go during the day when nobody was there,” she said. “They had this little roller-coaster. You would have thought it was King’s Dominion.” She pestered the ride operators so much, one man “put me up at the top of the Ferris wheel and left me there for 20 minutes,” she remembered.

“It was like the shows you would see on the ‘Ed Sullivan Show,’” she said of the fair’s entertainment and the Sunday night TV program that everyone in America watched back then. “I got to meet all kinds of people.”

“We had fireworks. When I say fireworks, I don’t mean little fireworks,” she said. “We had these huge rings. I could see them from the house” about a mile away. “They were over the trees. They were up in the sky. My grandfather, he was a first-class kind of a guy.”

Although it sounded like a melting pot of people, the fair was especially important to her community because in those days blacks were not welcome at local firemen’s carnivals or at movie theaters where white folks socialized. The schools were still segregated and people were not always cordial, to put it mildly.

“I really look back on those days and say, ‘We really had it going on,’ despite that they were ugly times,” she continued. “There were those KKK (letters) written on black churches. People would come and ask my grandfather to help to vote because they would get turned away because they couldn’t write their name, the ccould only make their mark,” she said.

When Zapata “got to a certain age, I didn’t want my mother to drop me off ” at school. “I wanted to start riding the bus with my friends.” But while she was waiting for her ride, a bus with white children would go by and kids would yell out the window. They called her the N-word and this and the other. “I was oblivious,” she said.

But her neighboring girlfriend wasn’t. “Don’t let them call you that,” she would tell Zapata. “Tell them to kiss your butt.” So when the bus came by again, “We would turn around and pat our buttocks. Growing up was interesting there. It is kind of ironic. It was some of my great memories.”

Now she brings her young grandson back to the family home on weekends so he can appreciate the area and the camaraderie.

The fair was started decades earlier by a conglomerate of people. Her grandfather bought it from them. “He started with the board as far as I know,” she said.

The fair was held on the third week in August starting after church on Sunday. “It was Gospel Day,” said Zapata. “The purse was given to local churches. Monday night was free to get in but after that, you paid every night. During the week most people came in casual clothes. Thursday night was like homecoming night. That was the big night. Everybody who moved away to the city came home. They were dressed to the nines, high heels in the dirt. The sheriff ’s department came to direct traffic. People parked to the entrance out to J. Edgar Road.”

The fair closed between 1966 and 1968. “My grandfather passed in 1960. My father ran the fair for a few years, Clifton Humbles, who started a funeral business,” she said. Then her grandmother, Justine Thomas, took over. But, Zapata said, “It was too much for her to handle. My grandmother could be very stern about things. She would get on the loudspeaker and say, ‘so and so you need to come up here and pay your lot fee now.’”

Zapata said when she was in the eighth grade she worked for her grandmother and supervised the high school boys who whitewashed fences at the fair. “She paid me $5 a day. She was paying everybody else a little bit more. We scraped bird poop out of the grandstand. I put my blood, sweat, and tears in it. Believe me, I loved that place.”

After the fair closed, Zapata’s grandmother held car races at the site for at least four years. “Then the insurance got to be too high” and that closed too.

“My grandmother was a very dynamic woman. Very smart. She raised a lot of money for the high school (Mary Nottingham Smith) and chartered two airplanes she took her science class to the Tennessee Valley Authority,” a power plant. She also took a group to the Boston Science Museum.

Zapata is gathering fair memorabilia. If anyone has any pictures to share send her a message [email protected]