This article first appeared in the Virginia Mercury. It is republished here with permission.

By Sarah Vogelsong

Virginia Mercury

A legislative attempt to force Virginia to reveal more information about COVID-19 outbreaks in the state’s poultry plants and other workplaces, introduced after months of stonewalling from Virginia health officials and their insistence that the plants are entitled to privacy protections, stalled Wednesday with no prospect of being revived until 2021.

The demise of the bill by Sen. Lynwood Lewis, who represents the poultry-heavy Eastern Shore, was another blow to workers and activists who have long sought details about the extent of the transmission of COVID-19 in poultry plants, which began in April and ultimately led to more than 1,200 cases and 10 deaths in largely minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities.

The measure would not only have required companies with five or more COVID-19 cases at a worksite to report those cases to the Department of Health but compelled VDH to issue a weekly public report on that information.

“It is a bad situation for workers and for the community to not know what is actually going on,” said Michael Snell-Feikema, a coordinator with Community Solidarity with Poultry Workers, one of several groups that have been fighting for greater state disclosure regarding the outbreaks at plants on the Eastern Shore and in the Shenandoah Valley.

“That’s not a good thing to be doing when you’re trying to build trust with the community about dealing with the crisis,” he said. “I think that the public and workers really have the right to know this, because it can be disclosed without violating individual privacy.”

Because Virginia health officials and Gov. Ralph Northam’s administration have taken a conservative — and much-criticized —approach to how much information they’ll disclose about coronavirus cases and outbreaks at individual businesses, it’s been difficult to unravel what unfolded in the plants during the chaotic early months of the pandemic.

However, information obtained by the Mercury through a Freedom of Information Act request paints a picture of anxious state and local health officials, including an Eastern Shore hospital, who were so concerned about the rapid spread of the virus at the Accomack County poultry plants that they advised shutting them down for two weeks.

That never happened.

‘Insisting that plants not be identified publicly’

The Virginia Department of Health says it backed away from the idea because of the deployment of a team from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to the region and mounting evidence that “strict adherence to administrative, engineering and personal protective measures” are effective in combating COVID-19. But emails obtained through FOIA show the department also faced pressure from the poultry industry, with the plants staunchly opposing two-week closures and one industry representative bristling at the idea that they were being “blamed” for the spread of the virus.

The emails also show the companies resisted the notion that the virus was spreading at their plants and were dead set against making information about outbreaks at their facilities public. “Companies have been cooperating but are insisting that plants not be identified publicly as having outbreak (sic) and do not want the results of facility-wide testing shared,” one state official wrote in another email.

Weeks later, one company would do an about-face: After plantwide testing at its Temperanceville facility, Tyson Foods announced that of 1,282 employees, 257 had tested positive — a 20 percent positivity rate. The majority of those workers were asymptomatic.

Still, Tyson Temperanceville remains an anomaly in Virginia. No other big poultry company in the commonwealth has released facility counts since the start of the pandemic. That doesn’t sit well with Lewis, who told the Mercury the public has the right to know how many cases are in individual plants.

Virginia officials have defended the policy of not revealing case counts for individual facilities where outbreaks occurred by citing state code provisions aimed at protecting the anonymity of individual patients, which Northam’s administration interpreted as extending privacy protections to facilities. While the Virginia Department of Health would later reverse that policy for nursing homes after bipartisan pressure, it has remained mum on poultry plants, insisting the state can investigate and handle cases in these facilities “without having to alert the general public.”

On the Eastern Shore, the poultry plants are “a huge part of our economy,” Lewis said. “And I respect that, and I am not trying to do anything that is anti-poultry industry at all. I’m talking about public knowledge and information in an extreme public health emergency.”

Nevertheless, Lewis on Tuesday told the Mercury he intends to let his legislation, the only bill put forward during the General Assembly’s special session on COVID-19 to address the dearth of public information on Virginia’s poultry plant outbreaks, die in committee. He pointed to several issues with the measure, including its inconsistency with emergency pandemic regulations for workplaces passed by Virginia’s Safety and Health Codes Board that order employers to report any positive cases to VDH within 24 hours.

Those regulations don’t include a public reporting requirement like that outlined in Lewis’s bill, the senator acknowledged. But he said he believes a better version of his legislation can be crafted by January, when the regular General Assembly session begins, and that in the meantime the Northam administration could be persuaded to change its interpretation of state privacy laws.

That “interpretation, I think, is open to interpretation,” he said. “And I think we can have some full and frank discussions as we go towards that.”

Limited resources, vulnerable populations, little information

As a population, meatpacking plant workers have been one of the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic. In June, rural news outlet The Daily Yonder found such plants were “the largest single factor in COVID-19 hotspots in rural America,” with the next largest being significant populations of non-White people.

A CDC report drawing on data from 23 states, including Virginia, found that in April and May, more than 16,000 cases of COVID-19 had been detected in 239 meat and poultry processing facilities. Of those, 87 percent of the cases were members of racial and ethnic minorities. Among the reasons cited by the CDC for the meatpacking plant spikes were “prolonged workplace contact,” workers’ tendency to share transportation and live in congregate housing, and “frequent community contact with fellow workers.” Others have hypothesized the low temperatures in packing houses let the virus survive longer in the air or that the plants’ sophisticated ventilation systems permit it to spread more rapidly and widely than in other settings.

Virginia officials were struck by the phenomenon. “Interestingly, these outbreaks continue to hit similar packing plant operations across the country but we don’t see similar outbreaks in manufacturing plants which do not include live animals but have similar work conditions,” mused Eastern Shore Environmental Health Manager Jon Richardson on April 22 in an email obtained through the Mercury’s FOIA request.

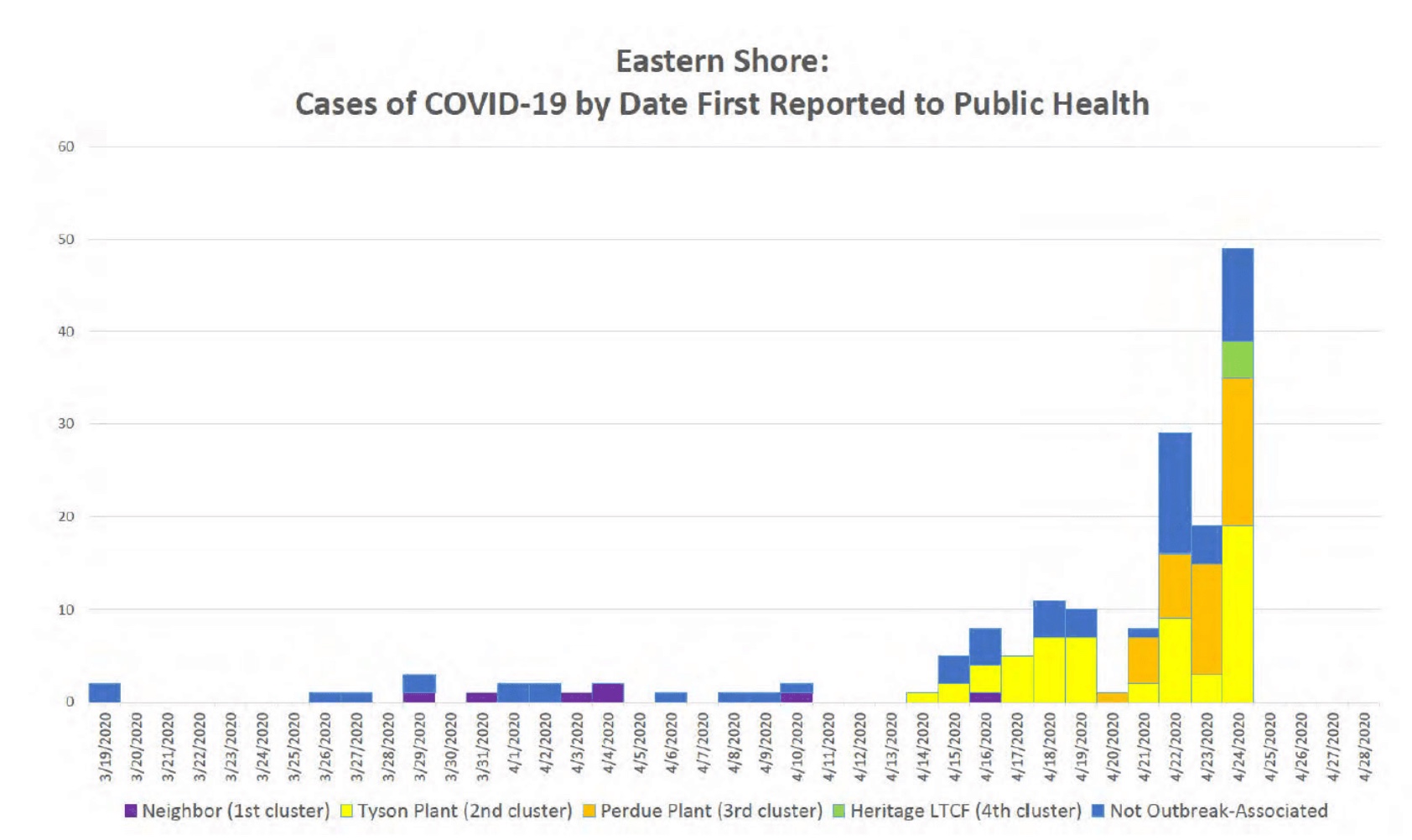

In the early weeks of the pandemic, Virginia would follow the pattern seen in the rest of the nation, with outbreaks emerging at the state’s poultry plants concentrated in the Eastern Shore and the Shenandoah Valley. By late April officials had identified outbreaks at 10 different plants owned by eight different companies in both regions; emails show a small outbreak would later be detected at an egg processing facility in the Mount Rogers Health District, southwest of the Shenandoah district. Numbers especially appeared to be ticking up at an alarming rate at the Eastern Shore’s two plants, the Tyson Foods facility at Temperanceville and Perdue Farms’ Accomac plant.

As in plant outbreaks elsewhere, officials realized that Virginia’s poultry cases were disproportionately spreading among minority populations. In the Central Shenandoah Health District in May, Hispanic or Latino people made up 42 percent of all cases, even though they represent only fractions of the population in each of the district’s localities. (Even in Harrisonburg, which has the region’s largest concentration of Hispanic people, the group constitutes only about 21 percent of the population, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates.) Today, Black and Hispanic people represent almost 60 percent of the majority-White district’s cases.

On the Eastern Shore, cases predominated among the Black population, which included a number of immigrants whose primary language was Haitian Creole. One epidemiological report from VDH covering March 19 to April 27 obtained through a FOIA request found that 68 percent of all COVID-19 cases at one of the region’s two plants affected Black people; at the other, the number reached 73 percent. A May 6 appeal from the Department of Health to the CDC noted that “the affected population is primarily African American, Hispanic and Haitian Creole, highly vulnerable populations.” Two early deaths related to the plants, one email from a health official noted, “were both members of our minority communities as was our previous death.”

From the beginning, officials were particularly concerned about the Eastern Shore outbreaks because of the rural region’s lack of resources and limited access to medical care. Its one hospital, Riverside Shore Memorial, has just 52 beds and six intensive care unit beds — a fact highlighted in an April 22 letter to VDH from Riverside Health System CEO and President Michael Dacey as cases began to surge.

That letter, as well as other documents obtained through the FOIA request filed by the Mercury in May, offers a glimpse into the escalation of the cases and how decision-makers handled them, although there are significant limitations. The Virginia Department of Health, for example, redacted many details of its internal correspondence in responding to the Mercury’s FOIA request, including nearly every instance of company names and representatives, making it difficult to determine exactly who state officials were meeting and talking with.

In justifying the redactions, VDH again cited privacy concerns, explaining, “In order to preserve the anonymity of individuals whose medical records have been examined by VDH as part of the investigation of COVID-19, the names of specific meatpacking and/or poultry processing facilities, identifying information concerning specific companies, and case counts related to specific facilities have been withheld pursuant to §32.1-41 of the Code of Virginia.”

Megan Rhyne of the Virginia Coalition for Open Government acknowledged that while “it might be easy to ID someone when the number of sick people within a facility is small,” she “continue(s) to disagree with (VDH’s) interpretation” of what information state code prohibits officials from sharing.

According to Snell-Feikema, the advocate for poultry workers, the privacy justification falls apart in the face of large numbers of cases. Regional data show that case counts for many poultry plants have numbered in the dozens to hundreds.

“There’s been larger numbers in the poultry plants … since very early on,” he said. “So that concern about privacy isn’t really there.”

At least one VDH official fretted that revealing case numbers could lead to stigmatization. In an email thread involving several Department of Health employees regarding an information request by a Bloomberg reporter, VDH Eastern Region Public Information Officer Larry Hill argued, “I think one point many of us are missing in a risk communications perspective is that we also have to keep in mind about stigmatizing a person, place, business or thing. I’m seeing a lot of it and somewhere it’s going to come to light.”

‘Our concern grows by the hour’

According to the emails obtained by the Mercury, the first case in a Virginia poultry plant was reported on April 8 by epidemiologist Stephanie Kellner of the Central Shenandoah Health District. The date of onset was estimated as March 29. Within days more notifications were rolling in for suspected cases in the Eastern Shore and Lord Fairfax health districts, the latter covering the northern part of the Shenandoah Valley.

The same day VDH received the first report of a case in a Shenandoah Valley plant, the department sent a letter to the facility advising that symptomatic people should be isolated at home, that the employer should offer flexible leave and not require a doctor’s note or lab test to confirm illness and that “if an employee is confirmed to have COVID-19 infection, employers should inform fellow employees of their possible exposure to COVID-19 in the workplace but maintain confidentiality as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act” (bolding in original).

Later that night, Kellner and Julia Murphy, a state public health veterinarian with VDH who eventually would convene and lead a work group devoted to the poultry plant outbreaks, pondered how to proceed.

“I really want to know whether/how they are implementing any social distancing and whether they will provide face shields,” Kellner wrote. “Also want to see in writing what they are doing with regards to sick leave for the ill.”

Within a week, cases were climbing precipitously, as an unredacted chart included in the Mercury’s FOIA revealed. On Friday, April 17, Richardson, the Eastern Shore environmental health manager, gave Virginia Health Commissioner Dr. Norman Oliver an update on one Eastern Shore plant, telling him investigators had confirmed “that there are workers infected from all parts of the factory.” In the same email, Richardson told Oliver he had spoken to someone at the plant’s corporate office and informed her of VDH’s policy of not identifying facilities. “I volunteered our regional PIO would be happy to work with their communications folks if they so desired,” he wrote.

Even as cases climbed, many workers remained unaware of the extent of the outbreaks. “Others from <redacted> voiced concern they were unaware of the <redacted> and were under the assumption ‘there was just one case,’” Richardson wrote Oliver on April 18. Workers in both Shenandoah Valley and Eastern Shore plants expressed the same concern to the Mercury in interviews over the following days.

Alarmed by the rapid spread of cases, officials moved quickly to find a way to contain them. According to summaries of calls and meetings, VDH repeatedly urged Tyson and Perdue to close their Eastern Shore plants for two weeks.

In an emailed account of an April 23 call, Richardson and Eastern Shore Health District Director Richard Williams “both agreed that <redacted> seems to have put in place all the measures they can to protect employees” but that “they may not be enough as the virus seems to continue to spread and it may be there are no further mitigations that can be put in place to help.” Williams “spoke of the incubation period of the virus and explained it was a risk-based decision but that human lives are at stake and that needs to weigh on the decision,” Richardson recounted.

VDH was not alone in calling for closures. Riverside Shore Memorial Hospital also encouraged the plants to close on a temporary basis, noting in a May 22 letter that “our concern grows by the hour.”

“Riverside believes that any steps that can be taken to prevent this situation from escalating should be taken immediately, including temporary closure of the plants to allow in-depth decontamination and staff quarantine,” CEO and president Dacey wrote. “Based on the surge in patients we are now seeing, we believe that the trajectory of the situation poses imminent health risks to the population and although we will take whatever proactive and reactive steps we can as a health system, we do not believe they will be sufficient to prevent substantial adverse outcomes to patients unless decisive action is taken immediately.”

‘The way they live’

Late on April 22, Tyson Temperanceville announced it would close for three days over the upcoming weekend for deep cleaning. But the industry bucked the suggestion that plants close for two weeks. One representative on the April 21 call, according to Richardson’s email, “didn’t like being ‘blamed’ for the spread of the virus.”

Nor did they want case information broadcast. An April 25 communication from Gena Berger, a deputy state secretary of health, observed that “companies have been cooperating but are insisting that plants not be identified publicly as having outbreak (sic) and do not want the results of facility-wide testing shared.”

In conversations with health officials, poultry representatives pushed back strongly against the idea that the virus was spreading in their facilities, contending transmission was predominantly through the community. An April 24 call summary from Richardson records a “Dr. Merrill” who acted as a medical adviser for one of the plants “stated that they believed the virus was spread through the community because of ‘the way they live’ indicating that the Hispanic and Creole populations tend to live several to a home and are continuing to attend church and other gatherings.”

“Dr. Williams replied that the data on the Shore does not agree with the transmission routes identified by Dr. Merrill,” Richardson wrote. “He explained we have asked our Central Office Epi team to take a look at our data but with more than 2/3 of our cases being from poultry plant workers it would be hard to conclude the plants were from community spread.”

That day, almost 70 percent of the cases reported on the Eastern Shore came from the Tyson and Perdue plants, according to the unredacted chart.

By then, officials, including the administration of Northam, who hails from Accomack County, were laser-focused on the Shore. On the evening of April 24, Virginia State Epidemiologist Lilian Peake emailed a contact with the CDC, which had already been in communication with Delaware’s Division of Public Health about poultry plant outbreaks.

“The governor’s office inquired whether a CDC team is available to assist Virginia with the poultry plant outbreak investigations,” Peake wrote. “Would that be possible?”

“That should be possible,” the CDC contact replied back.

As the CDC began to develop plans with Virginia, which would eventually lead to a team being deployed to the Delmarva Peninsula, officials mulled possible steps.

Putting quarantined poultry workers in hotels was identified as difficult due to inadequate capacity, but a suggestion from Oliver, the state health commissioner, to conduct point prevalence surveys met with more success. “At this point we have no experience or evidence base to guide decision making in meat-processing plants when dealing with a pathogen as contagious as this. This testing may really help,” Eastern Shore Health District Director Williams wrote.

Berger, the deputy secretary of health, wrote in another email thread involving officials from the governor’s office, VDH and the Virginia Department of Emergency Management that “I’ve also heard a clear directive that these two companies should not open until we are able to do a point prevalence survey on employees,” although she acknowledged that directive might change depending on what Maryland and Delaware chose to do.

Over the next few days, VDH would back away from its recommendation that the plants be closed for two weeks. By April 29, Williams was writing in a memo that VDH had “suspended the recommendation to close the plants, to maintain the critical food production infrastructure.”

By that time, the CDC team had been deployed to poultry plants in Virginia, Maryland and Delaware as part of a targeted regional mission, and President Donald Trump had issued an executive order attempting to ensure meat processing plants be kept running to limit impacts to the nation’s food supply.

The appearance of the CDC team, including industrial hygiene experts, would be influential in shaping Virginia’s response to the plant outbreaks, VDH spokesperson Maria Reppas told the Mercury.

“Control of health risks in industrial settings is the primary responsibility of industrial hygiene as a discipline — the VDH does not have industrial hygiene as a core discipline, nor do we have industrial hygienists in our personnel complement,” she wrote in an email.

“While not a primary driver of our decision-making process, President Trump’s executive order was consistent with our evolving thoughts, and supported our decision to rescind our initial plant closure recommendation,” she continued. “We felt viral transmission could be controlled in meat processing plants with assiduous attention and vigilant adherence to administrative, engineering and personal protective measures. This has proven true in the months since the outbreak began.”

A ‘policy marker’

Today, officials and observers say the outbreaks at the state’s poultry plants have slowed considerably. On July 30, when VDH began posting aggregate data on meat and poultry plant outbreaks, the state reported only nine cases related to such facilities that month. In April, by contrast, Virginia had logged 604 cases among meatpacking workers, while in May, the tally reached 550.

Anecdotally, Lewis said he sensed that “not many” cases remained in the poultry plants on the Eastern Shore, “nothing on the order of magnitude of where we started.” Snell-Feikema, the poultry worker advocate, concurred that cases seemed to have slowed in the Shenandoah Valley, although “Harrisonburg continues to have a fairly high level of COVID-19 cases.”

Last week Central Shenandoah Health District Director Laura Kornegay told the Daily News-Record in Harrisonburg that the region had experienced 366 poultry-related cases since the start of the pandemic. But unlike the Eastern Shore, no facilities in the Valley have voluntarily come forward with information.

“In the midst of all of this, the workers in the community were being left completely in the dark,” said Snell-Feikema. “I felt like the Shenandoah Valley really needed a comparable attention to what was being given to the Eastern Shore.”

While cases appear to have slowed in the plants, he worried that the situation could change with the arrival of the flu season and an influx of students to large campuses like James Madison University, a problem the Eastern Shore doesn’t face.

Absent legislation mandating reporting, the decision lies in the hands of the Northam administration. Lewis said that when it comes to releasing information about plant outbreaks, “there’s probably some room for discussion there,” despite the Department of Health’s repeated refusals on the issue over the last few months. If no changes occur, he’s prepared to file new legislation in 2021.

“Bottom line is, I think we’ve laid down a policy marker,” he said.

The Virginia Mercury is a nonprofit, nonpartisan online outlet based in Richmond covering state government and policy.